The Magician & The Metronome: Kagiso Rabada v Pat Cummins

Ahead of their World Test Championship meeting, Ben Jones reflects on two modern greats of fast bowling.

Jasprit Bumrah is the best Test seamer of his generation. Highly unorthodox, a master of the full repertoire of fast bowling skills, somehow still getting better game-by-game, the Indian is on a level above any other active quick bowler. Bumrah is a phenomenon, and nobody is close.

However in the tier below him, the battle for best-of-the-rest is hard fought. Some would make a claim for Josh Hazlewood. You may hear a few shouts for Marco Jansen, maybe another for Matt Henry, from hipster quarters. But the two clear stand-outs, the serious rivals for Bumrah’s crown, are Pat Cummins and Kagiso Rabada.

The comparison between the two is obvious. Cummins (32 years old) is a year or so older than Rabada, but it’s the scorecard similariy that draws the eye: the South African has 327 Test wickets at 22.00, the Australian 294 at 22.43. This week, they arrive at Lord’s to compete for the longest format’s biggest prize, the World Test Championship, each the star in their side’s attack.

Both men have achieved the status of modern great - but who is better?

****

First things first, both men do both thrive in all conditions. Their level of success away from home is almost identical, with Cummins averaging a smidge more on the road than Rabada. The South African has the superior record in Asia (averaging 25 against Cummins’ 30), but there isn’t a glaring hole in either’s record, no smoking gun for detractors on either side.

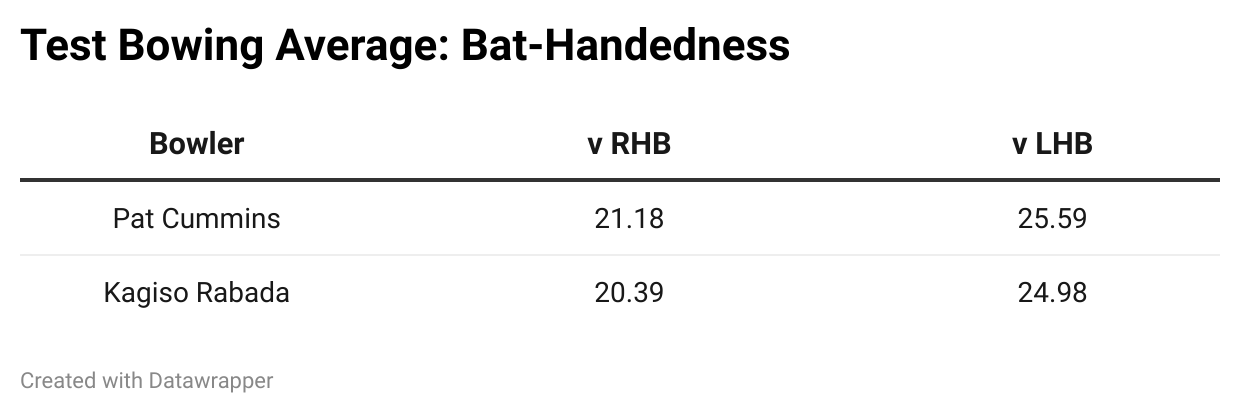

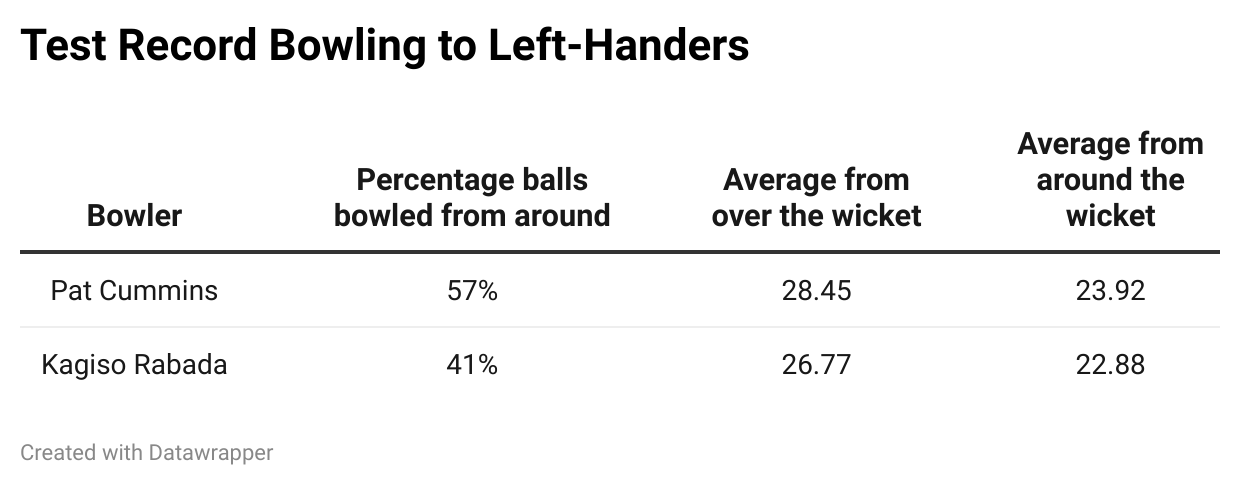

As you would expect for right-arm seamers, they both share a preference for bowling to right-handed batters, with natural angles keeping all forms of dismissal in play. In terms of their flexibility when taking on that unpreferred match-up, their willingness to change the angle to left-handers and effectiveness when doing so, they also stand together. Cummins is slightly more willing to come around the wicket, but they are both as effective as each other from this angle.

Away from the scorecard measurements, the physical components of their bowling are also eerily similar. In their early years, both were express quick, but have fallen away in the last three or four years. Their release heights are just 3mm different, their overall career average speeds (Cummins 138kph, Rabada 137.5kph) almost identical.

The first real divergence between them concerns lateral movement. Cummins doesn’t swing the ball - something he freely admits. In conversation with Tim Wigmore for their forensic Test Cricket: A History, the Aussie explained how “I never really try and swing the ball. I’m always looking for nip and, particularly in Australia, trying to get some bounce.”

That’s certainly borne out in the data. None of the established ‘greats’ of the last 20 years swing the ball less than Cummins, his average movement just 0.58°. To disregard a core tenet of fast bowling, and still average in the low 20s, is testament to Cummins’ mastery of another of those tenets - control of line.

Control of the line is Cummins’ “super strength”. Since the start of 2020, he hits a good line - defined as the channel outside off stump - with 69% of his deliveries, better than four balls an over. Not one seamer in the last five years can better that figure, and from that zone, movement is almost unnecessary. When Cummins hits that channel, he averages 21 - seam and swing movement or otherwise.

To say he “never” swung it isn’t quite right though. In the same chat, Cummins reflects: ‘When I was really young, swing was the only thing I was thinking about’. We can see it in that much mythologised debut in Joburg, where Cummins extracted 1.4 degrees of swing - he has never once matched that in a Test since.

It makes sense though. After that blistering debut, Cummins had a six year absence from the Test arena. Six years of physio and rehab, and further reflection. The bowling of a carefree 18 year old is almost always going to skew instinctive, aggressive, risk-taking. The bowling of a 25 year old who has had to fight to get fit to take on the toughest physical challenge in cricket - that is going to be rather different. The relentless channel-bothering, the refusal to put your returns in the hands of lateral movement and the uncontrollables that come with it, speaks to a man without overs to waste.

Equally, there’s other context. Barring his debut, Cummins has played his entire Test career as part of the Big Four, alongside Mitchell Starc, Josh Hazlewood, and Nathan Lyon. A discussion of “the greatest Test attacks in history” would be incomplete without referring to this Australian unit.

As you would expect, the players around Cummins have informed the bowler he has become. With Starc’s extravagant attacking lengths and movement, and Lyon’s unusually aggressive take on finger spin, Cummins and Hazlewood keep things neat and tidy, the best two bowlers in the group but with clear, regimented roles. Hit a line and length, keep the economy low and the scoring slow, and wait.

For Rabada, the story is rather different. Control may be something sought at times but in general, it’s an obstacle to his true calling - the relentless, all-consuming hunt for wickets. His economy may be the wrong side of 3rpo, but his strike rate - a wicket every 39 balls - is historically exceptional, the best for anyone with 150 Test wickets. He finds a huge amount more swing than Cummins, a dizzying 0.78°, and considerable seam movement to boot - no modern quick bowls as fast as Rabada while finding his amount of movement. It comes at the expense of controlling the line, and thus controlling the scoring, but the trade-off is a clear win.

It’s also, as with Cummins, a function of Rabada’s place in the team. Coming into the side at the end of a great era rather than the start, Rabada’s attack-mates have been far more inconsistent, both in identity and in returns. His most common bowling colleague is Vernon Philander, who’s played in 44% of Rabada’s Tests, with the next most frequent being Morne Morkel, at 27% - Morkel retired in 2018, Philander in 2020. Arguably South Africa’s two greatest fast bowlers, Rabada and Dale Steyn, overlapped for four years but only played 12 Tests together. He has played with some good Test bowlers, but Rabada’s proximity to the true greats of South African fast bowling - of Test fast bowling full stop - was brief. And for the purposes of this discussion, far briefer than Cummins.

By my count, in his Test career Rabada lined up in an attack with 20 different fast bowling teammates; depending on classification, for Cummins it’s just 10. Lyon has played in 96% of Cummins’ Test appearances, Starc 78%, Hazlewood 66%.

Rabada has always been encouraged to be the tearaway. Alongside the Steyn, Philander, Morkel triumvirate, he was able to bowl hyper-aggressively because of their consistent quality; in their absence, the second half of Rabada’s Test career, he’s taken on the responsibility of being the attack leader.

The company of excellence does cut both ways. For much of his career, Cummins has had to fight to take the new ball, usurped by those (like Starc) who exploit its unique movement more readily, and by those (like Hazlewood) who claim seniority. As captain Cummins has taken the new ball more often (34 times) than not (26), but it’s still clearly a conversation at best, a battle at worst. While Rabada may have found himself in similar shoes for the early part of his career, of late it’s different. Since the start of 2020, he’s almost exclusively bowled with the new ball; only once in 53 innings has he not taken it.

And yet that has not translated into Rabada dominating with that new ball. Indeed for the first 30 overs, Cummins is actually more effective than Rabada, before the trend reverses - pun intended - with the old ball.

From the 30th over onwards, Rabada is substantially better. This feels counterintuitive, given what we know about the lateral movement Rabada finds, but on closer inspection, we can see that he is still finding serious movement even with that old ball, with no discernible drop in swing movement.

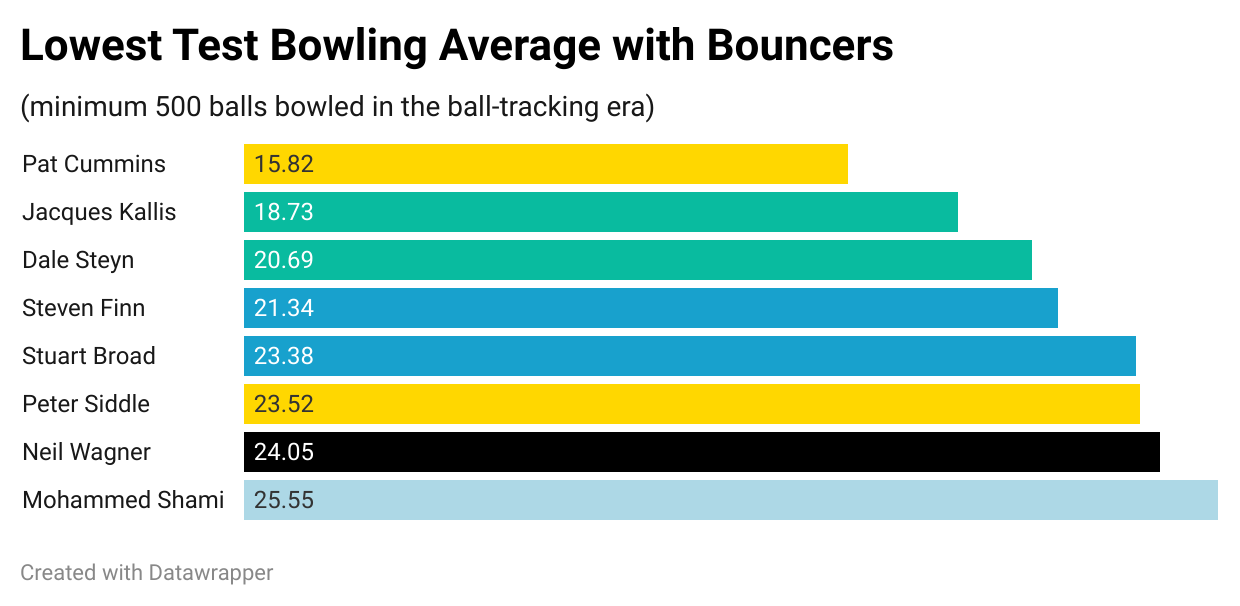

It’s interesting that old-ball struggles for Cummins aren’t a reflection of his short ball ability. Throughout his career Cummins has gone to the short ball very regularly, with just over 20% of his deliveries in Test cricket being bouncers - in simple terms, just over one an over. That is more than the average red ball quick for sure, but given he averages 16 when bowling them, it’s clear why he goes to that option so readily. No bowler in the ball-tracking era is a more effective bowler of the bouncer.

Turning attention to this week, both men have excellent records at Lord’s, and in England more generally, but Rabada may be the more optimistic of the two. Post-pandemic, Lord’s has been a venue with a huge amount of lateral movement; among the established UK grounds in recent years it has the highest average seam movement and the highest average swing to boot. There’s something for everyone - apart from batters, given it also has the lowest batting average against pace in that time - but given Rabada’s wider skillset when it comes to moving the ball, a venue that gives him more to play with is a boost.

Zooming out, there are obvious economic differences between the two. In a cricketing sense, Cummins is well remunerated enough by Cricket Australia that he is able to skip the IPL, entering only at optimal moments in the auction cycle, focusing on rest, operating at peak intensity as often as possible. Rabada does not have that privilege, given the economic realities of being a CSA employee. He has to be pragmatic, to bowl when he doesn’t want to, to play the game.

All this is to say that, regardless of the similarities between the two, they have taken different routes to get here - which makes our conclusion all the more remarkable.

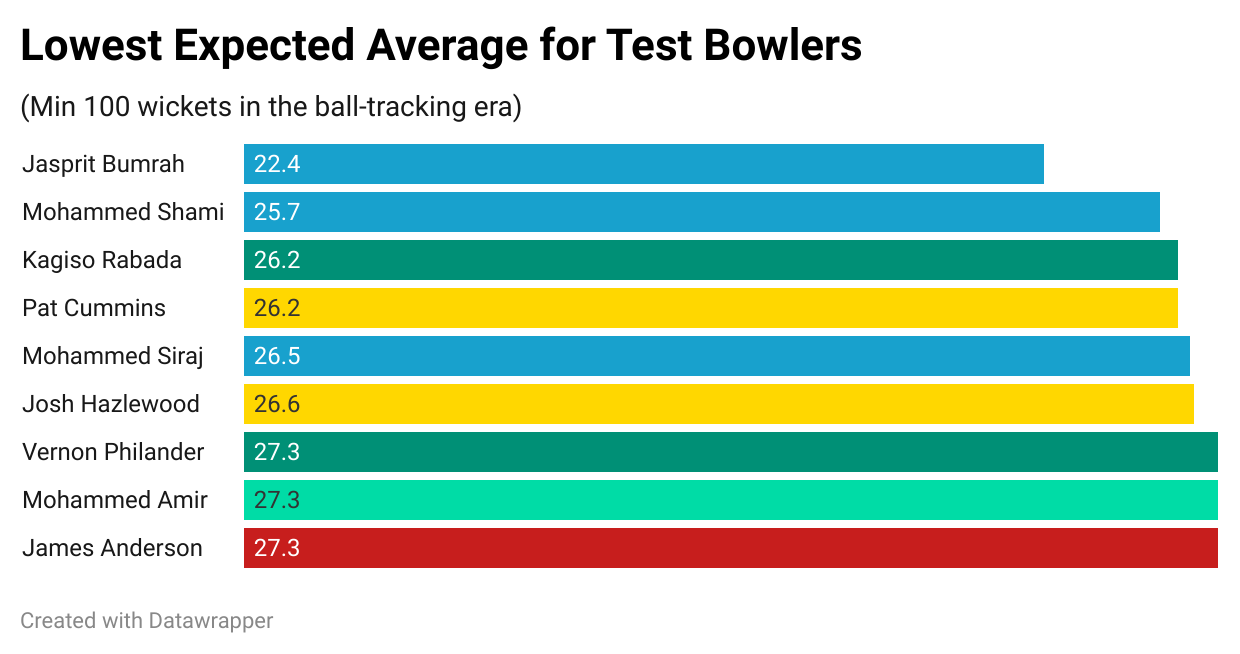

The CricViz Expected Wickets model takes the ball-tracking data for a bowler, and calculates the average returns those deliveries would get if bowled to a typical batter. It’s assessing every element of bowling - speed, accuracy, movement, bounce, and plenty more - to get a truer reflection of a player’s ability than the dots and dashes in the scorebook. According to that model, Rabada’s Expected Average is 26.2. Remarkably - almost unbelievably - so is Cummins’.

Every quality we’ve discussed, each attribute or preference, have come together to create two bowlers in Cummins and Rabada who are - remarkably - precisely of the same quality. Overwhelmingly similar, critically different, entirely equal.